Putting A&M's Best Foot Forward

Alan Cannon retires after 44 years of telling the stories of Aggie Athletics

Robert Cessna, The Bryan-College Station Eagle

story from the June 20, 2025 edition reprinted with permission of The Bryan-College Station Eagle.

Loyalty is hard to find in college athletics these days. Coaches and administrators have always moved around, but now athletes have joined them at an alarming rate.

That makes Texas A&M’s Alan Cannon a dinosaur. He started working for his alma mater in 1981 while going to school. He’s gone from being a student sports information assistant in baseball to being the executive associate athletic director for external operations.

The 63-year-old Cannon has decided it’s time to cut back on his workload with his last day in his current role (on June 30). He’ll take July off and return in August in a part-time role as a special assistant to the (athletic director)/historian/liaison to former players.

“It’s just time,” Cannon said. “The family has put up with me working really seven days a week for 10 months out of the year.”

And few did their job better than Cannon. He was inducted into the College Sports Information Directors of America (CoSIDA) in 2014, and in 2018 he received the Arch Ward Award given to CoSIDA members who make an outstanding contribution to the field of college sports information and has brought dignity and prestige to the profession. Cannon has been highly decorated by his peers because he helps others do their job.

“I think it’s the service aspect of what he does [that stands out],” A&M assistant athletic director Brad Marquardt said. “I think the hospitality that he brings to the press box, to his interactions with the media. I feel like that's the legacy that he’s built here. The media get what they need, and they have a good time doing it. He just treats them so well. I hope that continues forever, because, that’s the way it should be done, and that’s the way Alan Cannon has done it.”

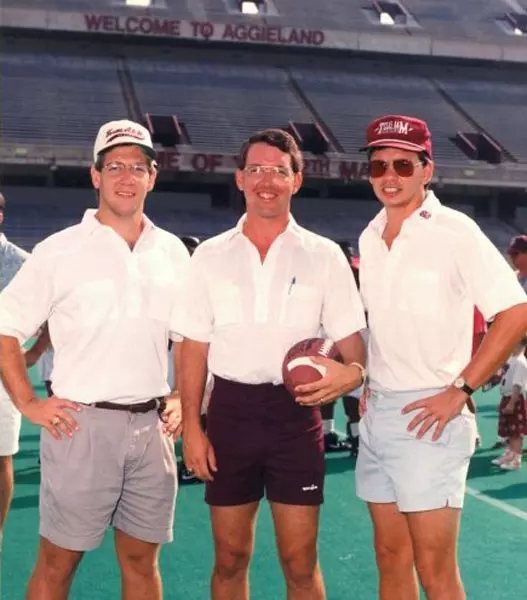

Cannon has the ability to please both his bosses and help the media, said Marquardt who worked for Cannon as a student assistant in 1987 and returned in 1990.

“It's a fine line,” Marquardt said. “It’s a tightrope that you walk. We work for Texas A&M. That’s a fact. We also want to help the media to be able to tell our stories. So, it’s a symbiotic relationship. You want to treat the media well, not to bribe them into telling good stories. But if they have a good experience, I think that’s going to factor in how things are portrayed here at Texas A&M.”

Marquardt built a lifetime of memories with Cannon that include the 1989 baseball season. That team is considered by some the greatest one not to win the College World Series. Marquardt had graduated but stuck around as kind of a graduate assistant for baseball, helping when needed.

“I just remember hauling sodas up to the press box, going up the stairs, because that’s the only way we could get there,” Marquardt said.

That season was a lot of fun until LSU’s Ben McDonald and the Tigers swept a doubleheader to win the NCAA Central Regional.

Cannon, though, was often at his best when things were the worst. Marquardt marveled at Cannon’s leadership skills during the Bonfire tragedy in 1999.

“There were are a lot of things pulling him around,” Marquardt said. “The players that we selected — that he selected — and just getting them ready to talk to the media [about Bonfire], the whole leadership [was amazing]. Because, as you remember, I mean, this place was overrun by media people, right? It was a lot to take in, and his leadership in that period was just really great.”

No one appreciates Cannon’s dedication more than retired Texas A&M football coach R.C. Slocum who served A&M for 53 years.

“I could just go on and on about him,” Slocum said. "He’s a special guy, and he really took great pride in his job. That’s a hard job. You deal with a whole bunch of different people, and all want to get into what’s going on. And to work as long as he did, I think the most impressive thing he did is how long he worked and the fact that he did it with so many different people. That’s the greatest compliment you could pay him is that [new] coach after [new] coach after [new] coach came in and [kept him]. It’s not unusual for a new guy to come in and say, ‘Hey, I want somebody in here I can trust. I want a new guy.’ And no one ever had any concerns about the trustworthiness of AC.”

Tom Wilson was the first head football coach Cannon worked with, and Mike Elko is the eighth.

“[Cannon] was totally loyal for the guys he worked for,” Slocum said. “And when the next guy would come in, he would say, ‘OK, my job is to work with this guy and to make things as good as I can make them for him.’”

Slocum worked with Cannon for 14 seasons as head football coach and he also worked with him for two stints as interim athletic director.

“I was so impressed [with Cannon],” Slocum said. “I’ve watched him over the years. When he worked for me, he had great respect with the guys [outside the athletic department] he worked with. They knew they could trust him, and he did what he could do to facilitate them, but never at the expense of the people who he worked for.”

Cannon was a high-energy guy, Slocum said.

“He runs every which direction during the [football] season, during the ballgames, after the ballgames,” Slocum said. “He’s been on a fast treadmill a long time.”

Cannon worked at a pace that even his staff had a tough time matching and student assistants had a rude awakening if they thought this was a sedentary job. Debbie Darrah, who retired in 2019 after 28 years as assistant director of media relations under Cannon, remembers one student finding that out the hard way.

“AC is such a fast walker, and there was a young student who wanted to shadow him at a football game,” Darrah said. “She came very professionally dressed. [Senior office assistant] Jackie [Thornton] and I were up in the press box back in the old stadium when it was on the other side. This was pregame, but we saw AC and this student down on the track on the sidelines. And we saw that she had heels on, and we both looked at each other and said, ‘Oh, this is not going to go well.’ And all of a sudden, he takes off walking like he's got to go get somewhere, and she’s trying to keep up with him, and he’s just leaving her in the dust.”

Cannon has been going like that since he made the baseball team as a walk-on. The 1984 marketing graduate was named the department’s director in 1989 and was promoted to assistant AD in 1999 and associate AD for media relations in 2003. He was promoted to his current post in May 2024. He was a team player, always doing what was asked of him.

“I go back to the way I was brought up with faith and family,” Cannon said. “I’m not a great writer, I’m not a great speaker, but I just grind, and I think my dad always stressed, give great effort, have a great attitude, and you'll do all right.”

Cannon said he couldn’t have lasted this long without a talented, creative full-time staff complemented by student assistants.

“I’m very blessed,” he said.

Yet, they were the ones who felt honored.

“AC is probably the main reason I stayed at A&M as long as I did,” Darrah said. “I never really wanted to look to go elsewhere. He always had your back. He was always willing to help out. He just was, and is, such a hard worker, and it made you want to work hard for him. You didn’t ever want to make him look bad, but if you ever screwed up, he was going to take the bullet for you. He always stood up for you and had your back. He wasn’t a micromanager. He let you do your job.”

If you wanted to vent, his door was open and he was all ears, Darrah said.

“He was just so well-respected across the country by everyone and the media,” Darrah said. “I doubt there’s anybody who had any qualms with him. He was just a wonderful person, very friendly, very respectful to everybody, I couldn’t have asked for a better boss.”

How it started

Cannon became aware of his chosen field while a senior in high school at Dallas Skyline.

“There’s a program called executive assistants that for you it’s basically an internship,” Cannon said. “I didn't even know sports information existed.”

Cannon worked as a volunteer in the program for SMU SID Bob Condron, who went on to become director of media services for the U.S. Olympic Committee for 28 years. Condron’s assistant was Maxey Parrish, who was Baylor’s SID from 1980-2000.

“They knew I was coming to A&M and wanted to try out for baseball, but Bob and Maxey said, ‘Hey, talk to [A&M SID] Spec Gammon, see if you can volunteer.”

Cannon walked on to the 1981 team, making the media guide, which pleased his parents, but he wasn’t going to make the starting lineup next year or the year after that.

“After that freshman year, Coach Chandler and I sat down and he said, ‘Hey, you and I both know you're not a big-league ball player,’” Cannon said. “It was in the way that Coach Chandler was always looking out for what’s best for me.”

Chandler suggested Cannon work for sports information and earn some money while he went to school.

“He said, ‘We don’t have anybody to do baseball, so you’ll go on all the trips,’’ Cannon said. “So, my freshman year, I went on one varsity road trip as walk-on, but from ‘82 on with baseball team, I was able to travel with them.”

Cannon, who came to A&M wanting to be an engineer, had to call an audible.

“After about six weeks of my freshman year, I realized my math and science background didn’t prepare me well enough for that,” Cannon said. “So, talking to some people here on campus, if sports information didn’t work out, maybe there’s sales.”

When he switched his major from civil engineering, journalism seemed the logical option, but he kept his options open.

“When I changed, it was, ‘Hey, do you want to go journalism; where do you want to go?” Cannon said. “Bob Condron at Texas Tech had been a marketing major with public relations as basically a minor. I thought, ‘OK, that's what I'm gonna do.’”

He went on the A&M payroll in May 1981, joining a whopping staff of four. Fred Battenfield was Gammon’s assistant SID in 1981. Jan Fambro was the secretary and women’s gymnastics coach, which was a club sport. DD Grubbs was the senior student assistant, and Cannon was the young student assistant “to cover all the athletes,” he said.

The best thing about Cannon’s job is it really has never changed, because it’s always been about the people.

“That’s the great coaches, the great staff, the great media,” Cannon said. “For me when I was getting into it, you're talking about the heyday of two papers in Dallas, two in Houston. Blackie Sherrod coming into the press box. You just go down the list. But to me, it really comes down to the players. You talk about baseball guys, in basketball when I was traveling with [coach] Shelby [Metcalf], football throughout the years.”

The players were Cannon’s age when he started, but now he’s got four decades on them, though it often doesn’t feel that way.

“I laugh, because I think in terms of, ‘Yeah, I'm still the same age,' because all these student-athletes come in and they’re ages 17 to 21 and then I see ‘em [later,]” Cannon said. “I mean, just today, I had a couple of guys that played on the 2000 football team, and we were talking, I was like, ‘Boy, that’s been 25 years ago?'”

The players never changed as far as Cannon was concerned. They can access information quicker than ever, but to him and his staff they’ve always been young people needing college to grow up.

“I hate to sound like Coach Chandler or [baseball] coach [Mark] Johnson or Coach Slocum, but you love to see the guys grow up and they become fathers and good people in the community,” Cannon said. “And that's what's so nice, such a pleasure.”

The toughest thing Cannon had to handle as a young SID was the death of walk-on place-kicker James Glenn in 1991. He collapsed before practice.

“Anytime we’ve lost a student-athlete it’s just crushing,” said Cannon, adding that “you try to be professional about getting the media the information as best you can, but taking into account their family.”

KBTX found out about the death and informed Cannon they’d be running the story. Cannon talked the producer into holding the news.

“I said, ‘Listen, if, if I were a relative of this young man, do I want to hear about this through the media, or do I want a phone call [from A&M]?” Cannon said. “I said, just give me an hour or two. And this was prior to internet, where we’re at now. So, he was courteous enough to say, ‘Hey, we'll hold it till, 5 o'clock or something like that.’”

Distributing news has changed greatly since Cannon’s first day.

“Back in the day, you knew your news cycle,” Cannon said. “You knew the morning paper deadline, the afternoon paper deadline, the radio [needs], the television [needs], you knew broadcast. So, you knew your windows. Now it’s 24/7, so there are no deadlines.”

Cannon and his staff have adjusted to the changes.

“I’ve always felt we’re the liaison between the media and the athletic department and trying to help you do your job,” Cannon said. “[To] give you as much background information, and trying to help understand your needs, [but] then never losing sight that you work for this institution.”

Cannon has said no on many occasions. He’s just delivering the message from a coach or administrator and media members understand that. Cannon had several interesting conversations with longtime CBS producer and Cannon’s “dear friend’ Craig Silver who would constantly request locker room access, knowing the answer probably would be no.

“He would just laugh,” Cannon said. “Because every week he would ask. And he’s just doing his job. And I told him, I said, ‘Craig, I'm going to go to Coach [Kevin] Sumlin; I'm going to go to Coach [Jimbo] Fisher. I’m going to go ask the question. I always felt like I needed to go back to the coach, because maybe he changed his mind, but Craig asked the question, so I said, ‘Let me go and ask the question as well.’”

Cannon almost left

Cannon basically had his car headed out of Bryan-College Station twice, but a sudden change each time kept him here.

Cannon’s tenure as a graduate assistant under Tom Turbiville was ending in 1985. Cannon had told Turbiville and those above him — assistant athletic director Ralph Carpenter and assistant athletic director John David Crow — that he’d be leaving.

“I told them that I’d given them the spring as a graduate assistant, but I had to have a full-time job because I just felt I couldn’t ask my parents to keep me on the payroll, so to speak,” Cannon said.

The A&M women’s golf team hosted the 1985 Southwest Conference championship at Briarcrest Country Club and Cannon was working what would be his final assignment. He had packed his 1972 Chevy Malibu and was ready to head home to Dallas. Kitty Holley’s Aggies won the tournament and as everyone was celebrating, Cannon also became a big winner.

“John David and Tom Turbiville, if I’m not mistaken, both of them came up to me and said, ‘Hey, we got you a full-time job. You’re going to be able to stay.”

Turbiville worked extra hard for several weeks to keep Cannon in Aggieland, because he knew Cannon would be a great SID.

“AC was meant for this job,” Turbiville said. “He has the temperament for it. He has the patience for it. He doesn’t get too riled up when it’s a job that the pressure would invite getting pretty riled or getting pretty stressed, but he never seemed to be over stressed. I think if you look at what the media in general say about Alan as being one of the best that they have worked with, that says a lot right there. Because media and SIDs – I’m still going to call it an SID, even though the title has changed many times over the years – the media and SID don’t always lend itself to a relationship being amiable, because it's a tough job.”

Turbiville spoke from experience, having worked at the Southwest Conference office for five years until getting hired as SID to work with football coach Jackie Sherrill for three years.

Turbiville wanted to hire Cannon, but A&M didn’t have enough money. Turbiville also knew SMU had an opening and with Cannon being a Condron disciple, it was put up or shut up. It took some work, but Turbiville managed to get free housing in a package to keep Cannon literally on the last day possible.

Turbiville started out as Cannon’s boss in title only.

“He was my mentor in reality, because he knew just from his time as a student assistant and working with Spec and then for a little while with Ralph Carpenter, he knew all the ins and outs of being an SID at Texas A&M,” Turbiville said. “I’d come from the conference office setting, which is a different deal than being with one school, and so he taught me a lot about how to be an SID, even though by title, I was his superior. But believe me, I pretty much did whatever and however AC led me in that first year.”

Four years later, Cannon felt ready to handle more responsibility. Those ahead of him were entrenched in their positions, but opportunity knocked. TCU SID Glen Stone needed an associate SID to handle football.

“So I went up there and interviewed,” Cannon said. “Coach [Jim] Wacker shook my hand, and slapped me on the back, and said, ‘I’m glad to have you.’ I got in my ‘84 Oldsmobile Cutlass and drove back down. Johnny Keith was the SID and [along with] Ralph, both of them called me in, shut the door and said, ‘Johnny’s going to the Houston Oilers. This job’s opening up. Would you be interested? And I said, ‘Absolutely, let me call TCU and tell them I’m sorry.’”

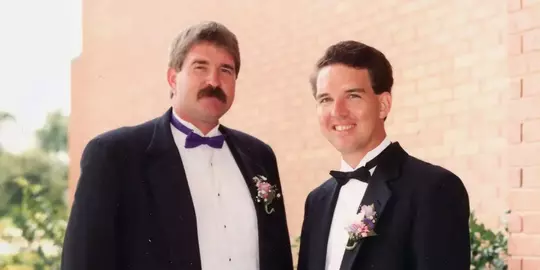

That was spring of 1989. Work and life came at Cannon fast. The A&M baseball team “was off the charts,” Cannon said, and he also met his wife, Kaye, that summer.

Cannon met his wife on a blind date along with former A&M trainer Mike “Radar” Ricke and his wife at the showing of “A Sweet Season,” a 35-minute video on the baseball season by Grubbs and KBTX.

Alan and Kaye raised two daughters who both graduated from A&M and are both kindergarten teachers following the lead of their mother, at College Hills Elementary.

Handling the superstars

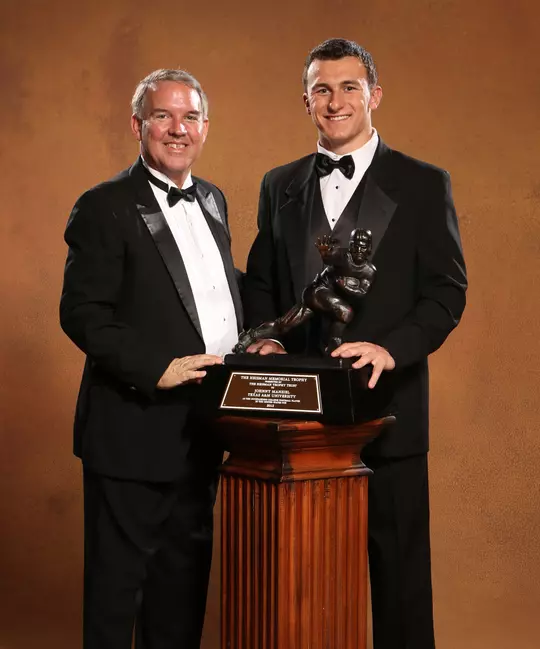

The most publicized athlete during Cannon’s tenure was quarterback Johnny Manziel, the first freshman to win the Heisman Trophy. It was him “because it was the initial part of the social media onslaught,” Cannon said. “But also going back in the late 1990s, with Dat Nguyen being a Vietnamese player, [that was a huge story]. I just give credit to the young people, both Dat and Johnny as well.”

Cannon and his staff were somewhat handicapped in promoting Manziel’s chances for the Heisman because Sumlin didn’t allow freshmen to talk to the media, but Cannon came up with a gameplan.

“We’ve got to make sure in our game notes we’re including all the tidbits [and] we’re comparing him to Heisman winners and how special a player he is,” Cannon said. “Because as an SID, this was the joke of, ‘OK, he wins the Heisman without doing an interview during the regular season.’”

The SID department helped it happen.

“I made sure with Coach Sumlin as soon as the regular season ends, we’ve got one week before the Heisman votes are in,” Cannon said. “We need to do a national teleconference, so everybody gets the same shot at him, and then the very next day, let’s do one at Hagner Auditorium there in the Bright Complex.”

Manziel helped as much as possible.

“I give Johnny credit in that he communicated with me very well, and so I never had an issue,” Cannon said. “He understood these are the parameters that Coach Sumlin wanted. And he said, ‘Hey, I trust you to lead me in the right direction.’”

The SID department has always been about promoting all its coaches and players which is much different in 2025 than 1981.

“Our role, when I started, is to be able to promote this university and this athletic department,” Cannon said. “[To do that] you had to work through the media to get your message out, and now you don't, necessarily [have to do that], We have our 12th Man Productions and our graphic people and our photographers, so that’s a major change.”

What hasn’t changes is the players and how they handle them.

“I still go back and being a father, the kids are still kids, and so they’re looking for that direction,” Cannon said. “And not to single out anyone, but there are several guys on the football team that have said, ‘AC, we appreciate the job you do, because you help us prepare for interviews.’”

Typically, it’s something small, such as wearing a shirt of an athletic company not endorsing A&M.

“And that's the gratifying part of the job, is when the young people say, ‘Hey, thanks,’” Cannon said.

Oh, the book Cannon that could write, but don’t expect it in your local bookstore.

“He just loves A&M,” Darrah said. “If there was something confidential, he wasn’t going to say anything to anybody, and I can’t imagine all of the stories that he has, that he’s going to take with him to his grave, just because he wasn’t supposed to tell anybody about it. You knew that he was someone you could tell him stuff, and it stopped with him.”

A new chapter

Cannon’s role was expanded by new athletic director Trev Alberts when he was hired in March 2024.

Cannon added an external piece that included overseeing 12th Man Creative and 12th Man Productions, the photographers and the marketing group as part of the transition within the athletic department.

“But after the bowl game [in December], Trev and I had a conversation about, that’s really not my niche,” Cannon said. “If I was going to hang on, it would just be football related.”

That idea got more traction in the spring with second-year football coach Mike Elko interacting more with former players who wanted to get more involved with the program, some sending their sons to camp. So, hooking those folks up with Cannon made sense. He’s the perfect liaison for several decades of players and their families. He’s really getting back to his grass roots.

Cannon learned loyalty from his father, Bobby Cannon.

“My dad started at age 13 working for Wyatt Food stores in Dallas, a small group,” Cannon said. “It was bought by Kroger [in 1958], and Mr. Wyatt said, 'As long as you keep all the employees that want to work for Kroger, we're OK.' So my dad from age 13 to 63, 50 years he was with the Kroger Company.”

A&M was somewhat like Wyatt Food when he started and now it’s Kroger.

"Athletics was kind of the family business that is now more of a corporation,” Cannon said. “I'm not saying good or bad. It's just different the way it is. And I go back to with Coach Slocum, John David Crow [and athletic director] Wally Groff, giving me the opportunity as the head guy in ‘89 and we would have our Friday night get togethers [with the media] at Tom's Barbecue, and Coach Slocum would come by and see us. But it was, it was just different back then.”

As a historian, Cannon can tell future Aggies how it was then and how it is now. Cannon said he hasn’t ever stopped to think about how many A&M coaches and athletes he’s come into contact with over the years. If Cannon gets bored with a lesser workload, he might want to start adding them up, but then his new gig will allow him to keep meeting people telling them what’s great about A&M, something he’s very good at. Slocum told Cannon he was happy for him.

“He’s been grinding for a long time and deserves a little less pace,” Slocum said.

Memorable Moments

Best road trip as an SID: “It was probably with [men’s basketball coach] Shelby [Metcalf] and [assistant] John Thornton. That would have been 1987. We left here and played a tournament in Sacramento, Calif. We went from there to San Francisco and then we flew to Honolulu, Hawaii. I know that was the first Christmas away from family. I hadn’t met [my wife] yet, but it was the Rainbow Classic. And the crazy thing is we played SMU in the final game in Hawaii. We flew back to Dallas. I got off the plane and worked the Notre Dame game in the Cotton Bowl Jan. 1 of ‘88. And then that next week, we played SMU, I think in College Station. With that road trip, I remember John Thornton myself and [A&M radio announcer] Dave South jogging across the Golden Gate Bridge.”

Worst football travel story as an SID: “After we won the Big 12 Championship in ‘98 the charter is coming back from St Louis. It’s late, and we’re coming down [to land]. And you kind of get used to the area [while landing] and we’re coming down, it’s like this, ‘This is not right.’ And we’re coming down lower, lower, and lower and the next thing you know, the pilot kicks it up, and we make a big U-turn. He goes, ‘Sorry, folks, we were going to the wrong airport,’; it was Bryan’s Coulter Field — with a large jet that would have been trouble.”

Worst basketball travel story as an SID: “Shelby again. We had played TCU. We bused back from Fort Worth to College Station. We slid off the road on Highway 6 between Hearne and College Station, and we slide into the ditch. And if I’m not mistaken, I think Lynn Hickey is in the ditch and a highway patrolman is in the ditch. The highway patrolman comes on the bus and says, ‘Folks, we’re going to try to get y’all back to Hearne, but you may be on this bus tonight.’ John Thornton and I and one other assistant said, ‘We’re not staying on the bus.’ We started walking, and it’s icy, and luckily, we just got a couple of miles down the road, and a four-wheel drive picked us up and got us back. But the team didn’t get back for another day or two.”

Memorable baseball trips: Cannon said no one could tell stories like former coach Tom Chandler. You didn’t have VHS or DVDs back then, but you didn’t need them. “Coach Chandler, and just the bus ride and hearing his stories and things were terrific,” Cannon said. “But we played the San Antonio Dodgers in San Antonio in an exhibition game, and the Dodgers let us travel in their bus, which had this one TV with a VHS. So, I thought, ‘Man, this is, this is high rolling. [It was] fun stuff, fun stuff.”

Up Close

- Favorite movie: Field of Dreams

- Favorite TV show: Cosby Show

- Favorite book: Anything with Lou Gehrig

- Hero: father

- Playlist: A little country, George Strait, Reba, a little Motown, the Temptations.

- What are your hobbies? Reading books, especially about World War II; running, which has become walking; and soon to be more golf